The History

The story of Honory & Sacrifice exists within a framework of the history of Japan and the United States during the 20th century. We provide some background on that history here. For a timeline of important events, including those affecting Roy Matsumoto, click here.

The Journey to America

The first Japanese immigrants came to Hawaii shortly after the end of the American Civil War as contract laborers, work on sugar cane plantations. By the late 1800s, Japanese workers were arriving by the hundreds in western ports in San Francisco and Seattle, many finding low-paid work on railroads and in sawmill operations, fish canneries, and domestic service. The majority of Japanese immigrants, however, found jobs as migrant farmworkers.

Japanese Farming and American Racism

Many farmworkers dreamed of starting their own farms. Those who were able to secure even poor and unproductive land used generations-old practices to reclaim it and make it productive.

Laws regulating land and agriculture made it difficult for Japanese farmers to access the resources necessary to participate on equal terms in the farming industry. The 1913 Alien Land Act, prohibited “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from purchasing land or leasing it for a period of more than 3 years. By 1918, despite these challenges, almost 90 percent of California’s strawberries, asparagus, celery, and tomatoes were grown by Japanese, a success story that aroused jealousy and racist animosity among White farmers. Even the courts supported discrimination against Asian farmers, with a 1923 case making sharecropping illegal because it was a way for Asian Americans to indirectly possess and use land. The Alien Land Act was not declared unconstitutional until 1952.

Despite widespread discrimination, Japanese communities began to spring up in such cities as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Tacoma, Portland, and Salt Lake City. Most Nisei children attended public schools, and some were enrolled in American colleges. “Japanese schools” which were after school or Saturday programs were also founded where Nisei learned Japanese customs, sports, and language. However, some Nisei were sent back to Japan for education and returned to America. They were called Kibei, literally “return to America”.

The Great Depression

To counter discrimination, Japanese Americans from California, Oregon, and Washington came together to form the Japanese American Citizens League in 1929 to fight discrimination and provide self-help to their community. In 1930, the first convention of the JACL was held in Seattle, WA. These organizations helped support the community during the decade of the Great Depression, when Japanese and other Asian minorities were often scapegoated as economic competitors and victimized by violence caused by race-based hatred..

World War II

President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked Congress to declare war on Japan the day after the December 7, 1941, Japanese attack on the U.S. naval base in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. FBI agents immediately began to round up and arrest Issei community leaders in Hawaii and the mainland for detention without cause or due process, based mainly on racist war hysteria. The government had actually commissioned a secret study called the Munson Report that indicated Japanese Americans were loyal to the United States, and would likely remain so even if the US went to war with Japan.

Despite this report, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, authorizing the War Department to forcibly remove Japanese Americans from “prescribed military areas,” which included all of California, Washington, and Oregon, and parts of southern Arizona. The Army began to move Japanese Americans out of these areas on the pretext that they were a threat to national security. More than 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry living on or near the West Coast were soon imprisoned in government-run concentration camps. Most of them were U.S. citizens or legal permanent resident aliens, and half were children.

In the camps, families were often separated, and family and cultural dynamics disrupted. The housing was substandard, with inadequate nutrition and health care. Most of those sent to the camps lost their homes and their livelihoods were destroyed. Some Japanese Americans died in the camps due to inadequate medical care and the emotional stresses they encountered. Several were killed by military guards, supposedly for resisting orders.

According to a 1983 report issued by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, the internment actions “were motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” The emotional and physical suffering caused by their camp experience affected many Japanese American families long after their release.

Japanese Americans in the U.S. Military

The Fourth Army Intelligence School was opened in late 1941 at the Presidio of San Francisco, about a month before the Japanese military bombed Pearl Harbor. Sixty students led by four Nisei instructors began training in the Japanese language.

In early 1942, the War Department declared that all Nisei are “enemy aliens not desired for the armed service” and classified them 4-C. Many of the over 5,000 Nisei in the armed forces are discharged. The War Department announced that it will not “accept for service with the armed forces, Japanese or persons of Japanese extraction, regardless of citizenship status or other factors.”

Despite the position of the War Department, Elmer Davis, director of the Office of War Information, recommended to President Roosevelt that Japanese Americans be allowed to enlist for military service, providing the initiative for the concept of an all-Japanese American military unit.

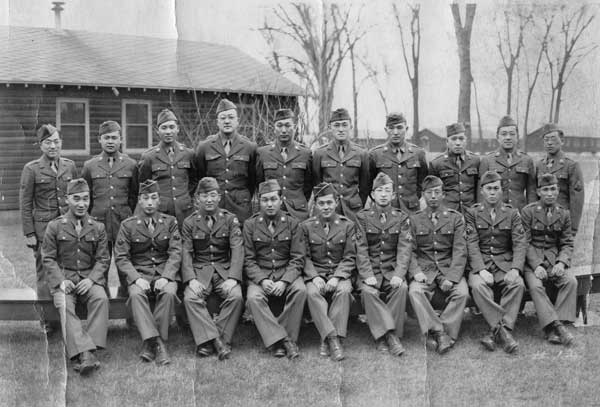

By 1943, Nisei volunteers and draftees from Hawai’i were organized into the 100th Infantry Battalion. Nisei from the mainland, most of them volunteering from behind barbed wire, began training as the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Later, the 100th merged with the 442nd and fought in Italy, France and Germany, playing a key role in the Allied war effort. Among the best-known missions of the 442nd was the rescue of the “Lost Battalion,” a group of 200 Texans surrounded by the Germans with no hope of escape. This heroic action resulted in more casualties to the 442nd than the number of those they rescued. The 442nd was the most decorated unit for its size and length of service in U.S. military history. Their famous motto, “Go for Broke”, succinctly expresses the typical attitude of the Nisei soldier, who was willing to give his all for his country.

In 1943, the Army language school was moved to Camp Savage, Minnesota, and becomes known as the Military Intelligence Service Language School (MISLS). The MISLS recruits several hundred Japanese American volunteers from concentration camps and from Hawai‘i, including Roy Matsumoto. Over 6,a000 students eventually graduate from the MISLS in a total of 21 graduating classes.

Merrill’s Marauders

A call for volunteers for “A Dangerous and Hazardous Mission” was answered by approximately 3,000 American soldiers. Organized into six combat teams, two to each battalion, the volunteers came from troops across the globe. Fourteen Japanese Nisei linguists trained in Military Intelligence were also part of this group. The Unit was officially designated as the 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional) with the Code Name: “GALAHAD”. They were later popularly known as Merrill’s Marauders named for their leader, Brigadier General Frank Merrill.

After preliminary training operations were undertaken in great secrecy in the jungles of Central India, the Marauers began the long march up the Ledo Road and over the outlying ranges of the Himalayan Mountains into Burma. The Marauders, with no tanks or heavy artillery to support them, walked over 1,000 miles through extremely dense and almost impenetrable jungles. They carried all their equipment and supplies on their backs and on the backs of pack mules. Re-supplied by air drops, the Marauders often had to make a clearing in the thick jungle to receive the supplies.

Wounded Marauders had to be carried on makeshift stretchers and evacuated by air, an extraordinary feat in itself. The Marauders would hack out a landing strip for the small evacuation planes. The air rescue unit would then land and take off in very hazardous conditions. The small planes, stripped of all equipment except a compass, only had room for the pilot and one stretcher.

In five major (Walawbum, Shaduzup, Inkangahtawng, Nhpum Ga, and Myitkyina) and thirty minor engagements, the Marauders defeated the Japanese 18th Division, who vastly outnumbered the Marauders. Roy’s heroic actions at Nhpum Ga saved the 2nd Battalion. The Marauders behind-the-lines operations culminated in the capture of Myitkyina Airfield, the only all-weather airfield in Northern Burma at that time.

At the end of their campaign, all remaining Marauders still in action were evacuated to hospitals suffering from tropical diseases, exhaustion, and malnutrition. The medical tags on their battered uniforms read “AOE”, for “accumulation of everything”.

For their accomplishments in Burma the Marauders were awarded the “Distinguished Unit Citation “ in 1944. The Marauders also have the rare distinction of having every member of the unit receive the “Bronze Star.” Roy Matsumoto was also awarded the Legion of Merit for his actions at Walawbum, but not for his heroic actions at Nhpum Ga.

After WWII

Members of the MIS provide translation services for war crimes tribunals and trials, and continue to serve during the Occupation of Japan in military government, civil affairs, education, and intelligence through 1952. Roy Matsumoto was stationed in Okinawa, Japan during this time until 1952.

In 1994, Roy Matsumoto was inducted in the “Ranger Hall of Fame” at Fort Benning, GA, and in 1995, inducted into the “Military Intelligence Hall of Fame” at Fort Huachuca, AZ. He received the Congressional Gold Medal in 2011 along with the Nisei veterans of WWII in the 442nd , 100th Battalion, and Military Intelligence Service.

To stay on top of current news, screenings, and announcements, please sign up for our newsletter in the right-hand column of this page.